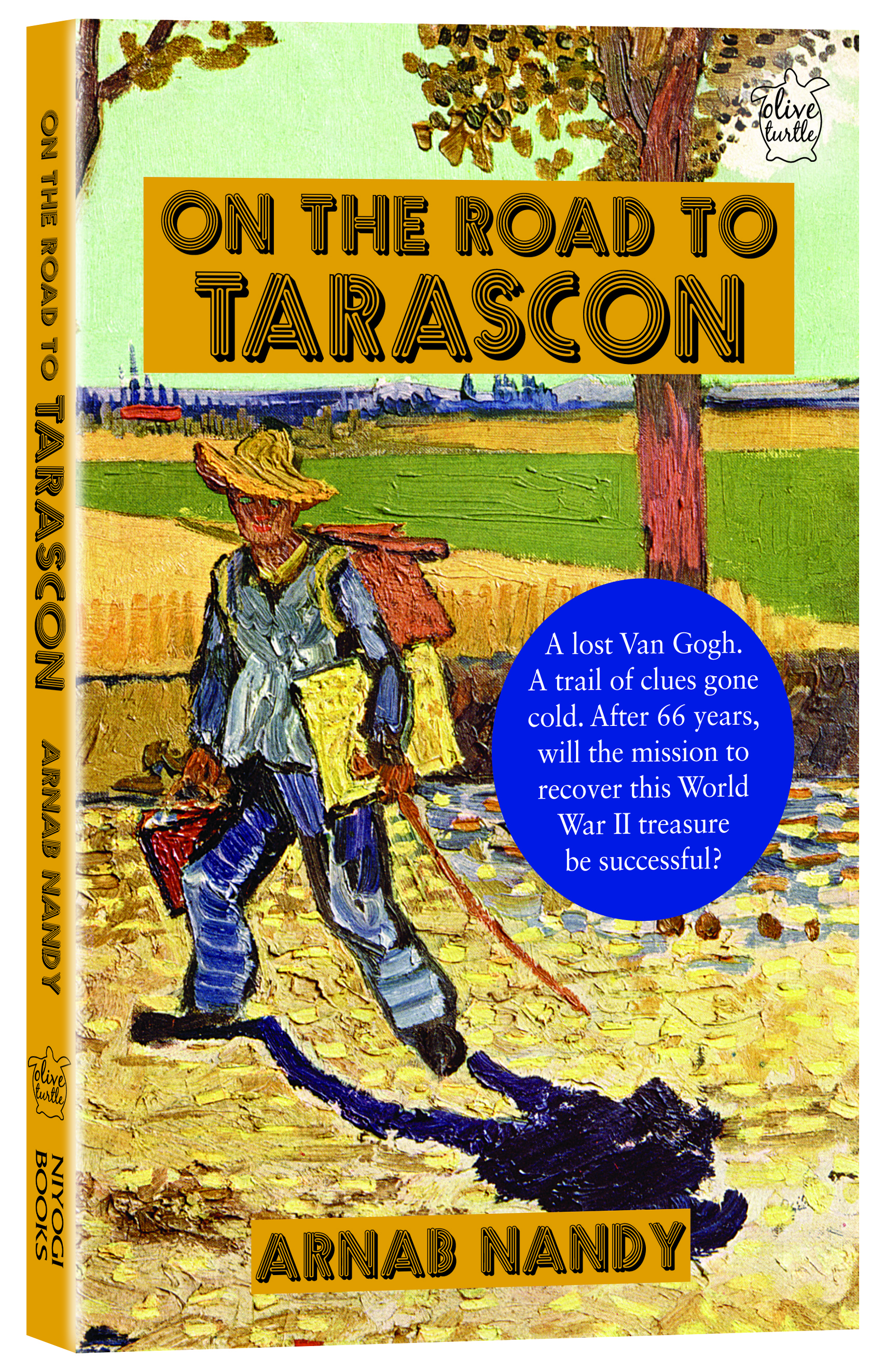

A lot of people go to Germany for war tourism. I go because I love the food and the people there. But this time, I went to research my first novel. The historical fiction novel is called ON THE ROAD TO TARASCON.

The Internet had different and sometimes conflicting versions of the bit of history I was interested in. So, I decided to go to Magdeburg — a town one hour and 40 minutes by train from Berlin — and find out for myself the circumstances in which a Vincent Van Gogh masterpiece had gone missing on April 30, 1945.

If you have an idea about the World War 2 history of Magdeburg, you would know it was completely flattened by the British Royal Air Force bombings in 1945. As I got down from the intercity express and walked into the city to find a tram to take me to my hotel, I kept imagining how the place would have looked in the early months of 1945.

Magdeburg could be boring, especially if you go there after spending time in the throbbing Berlin. At least, so my friend Kloot, who stays there, told me. But I had not gone to this city as a tourist. I needed some specific information and even though it looked nothing like 1945, I still wanted to walk around town, spend time at libraries and talk to the local people to be able to imagine a little better the times of the war.

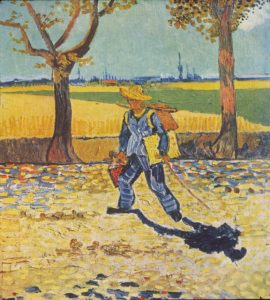

Van Gogh’s self-portrait The Painter on the Road to Tarascon was unusual in the sense that it was a full profile of the master, different from the usual half ones he drew sitting in front of a mirror.

Since the time the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum acquired the painting in 1912, it was on display continuously in its Fine Arts Gallery till 1943, when the decision to move the paintings was made to save them from bombings by the British Royal Air Force.

Consequently, more than 400 paintings from the museum’s collection were stored inside the Staßfurt (pronounced Stassfurt) mines in 1943.

In 1945, after the Americans took control of the mining town, two fires took place at the mines on 12 and 30 April, record declassified US military documents. The painting is supposed to have been destroyed in the second fire.

There is no clear evidence of how the fires caught—whether by accident or design. Dr Tobias von Elsner of the Kulturhistorisches Museum (earlier known as Kaiser-Friedrich Museum), Magdeburg, believes they were likely to have been arson, and started as a diversion to loot the priceless artworks. The Van Gogh painting was the most important one in the museum’s collection and this made it particularly attractive to looters. But who exactly the looters were is difficult to say. They could have been American soldiers, Nazi officials, German civilians or forced labourers.

Evidences that have surfaced over the years indicate that some of the paintings may have survived.

According to a report in the September 2009 edition of The Art Newspaper, a manuscript by Martin Luther, which had been stored at the Stassfurt mines, was handed over by an American soldier to a military chaplain in 1945. This was later deposited at the Concordia Historical Institute in St Louis, Missouri, US. It was returned to Magdeburg in 1996. An 1829 painting by the German artist Carl Hasenpflug — recorded to have been stored in the mines (though, the report says, it’s not impossible that the painting had actually been stored in the vaults of the central bank in Magdeburg) — surfaced in 1950. Some partially burnt documents and artefacts were also recovered from the mines.

The Staßfurt mines stopped production in 1972 and were sealed. It is now impossible to enter the chambers where the paintings had been stored.

The Kulturhistorisches Museum authorities have been appealing to people who might have any information regarding the whereabouts of the painting to come forward.

The plot of my book, a historical fiction named ON THE ROAD TO TARASCON, is based on these true events. Have a look at the cover below!

To order your copy on Amazon India, click here.